PREVIOUS: GREECE-IRELAND-ENGLAND

AMERICA 1869 -1890

NEW YORK 1869

Lafcadio Hearn arrived in New York late in 1869. Throughout his life he never mentioned these first few weeks in America. Nearly broke he made his way to Cincinnati.

CINCINNATI 1869-77

Hearn at 23 in Cincinnati.

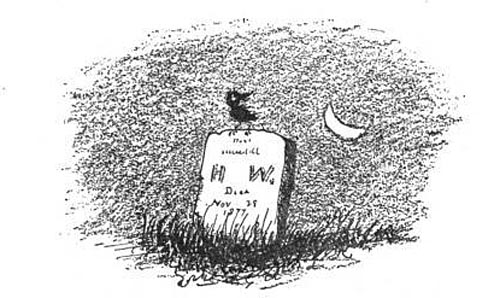

Hearn arrived in Cincinnati hungry, tired, unkempt,and without money. He was 19. There he became close friends with an older man, Henry Watson, who got him a menial job at his printing shop and eventually helped him to get a position as a "reporter" on the Enquirer, through some "feature" articles Hearn had shyly deposited upon the chief editor's desk.

Henry Watson would remain his close friend for the next 20 years, and Lafcadio's affectionate letters to the "Old Man" are the main source of our knowledge from those years.

MEMPHIS 1877

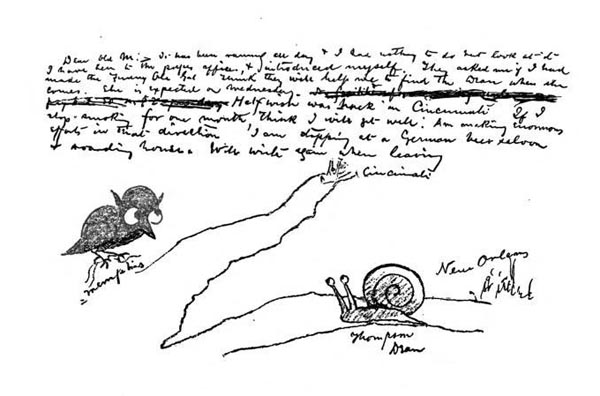

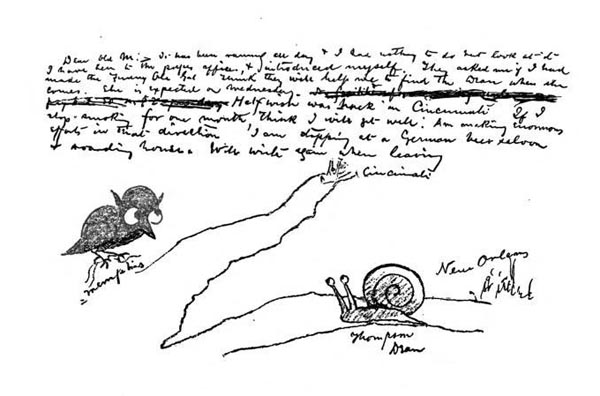

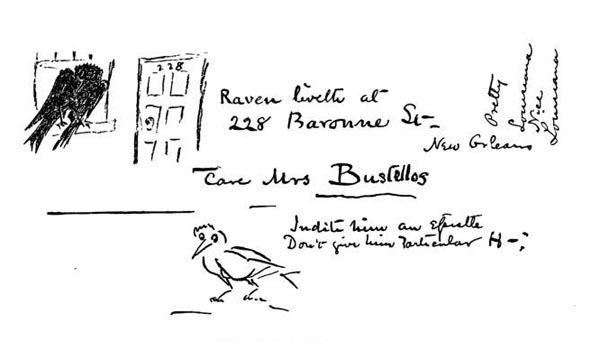

A LETTER FROM THE RAVEN

Lafcadio left Cincinnati for New Orleans in 1877. He went by rail as far as Memphis and then used the steamer "Thompson Dean" down the Mississippi to New Orleans. As usual he was penniless, and when the steamer was late, he had to wait a week in a dismal hotel at the harbor front. In his morose mood he wrote a letter to his old friend Henry Watkin illustrated with a prophetic drawing of the "Raven", a name Watkin had given him on account of his black hair and gloomy visions:

The drawing shows the confluence of the Ohio River and the Mississippi, the snail is labeled "Thompson Dean". It is dated October 31, 1877.

"DEAR OLD DAD : I am writing in a great big,

dreary room of this great, dreary house. It overlooks

the Mississippi. I hear the puffing and the

panting of the cotton boats and the deep calls

of the river traffic; but I neither hear nor see the

Thompson Dean. She will not be here this week,

I am afraid, as she only left New Orleans to-day.

My room is carpetless and much larger than

your office. Old blocked-up stairways come up

here and there through the floor or down from the ceiling, and they suddenly disappear. There

is a great red daub on one wall as though made

by a bloody hand when somebody was staggering

down the stairway. There are only a few panes

of glass in the windows. I am the first tenant of

the room for fifteen years. Spiders are busy spinning

their dusty tapestries in every corner, and

between the bannisters of the old stairways. The

planks of the floor are sprung, and when I walk

along the room at night it sounds as though

Something or Somebody was following me in the

dark. And being in the third story makes

it much more ghostly.

I had hard work to get a washstand and towel

put in this great, dreary room; for the landlord

had not washed his face for more than a quarter

of a century, and regarded washing as an expensive

luxury. At last I succeeded with the assistance

of the barkeeper, who has taken a liking to

me.

I am terribly tired of this dirty, dusty, ugly

town, - a city only forty years old, but looking

old as the ragged, fissured bluffs on which it

stands. It is full of great houses, which were once

grand , but are now as waste and dreary within and

without as the huge building in which I am lodging

for the sum of twenty-five cents a night. I am

obliged to leave my things in the barkeeper's

care at night for fear of their being stolen ; and he

thinks me a little reckless because I sleep with

my money under my pillow. You see the doors

of my room - there are three of them - lock

badly. . . . They are ringing those dead bells every

moment, - it is a very unpleasant sound. I suppose

you will not laugh if I tell you that I have

been crying a good deal of nights, - just like I

used to do when a college boy returned from vacation.

It is a lonely feeling, this of finding oneself

alone in a strange city, where you never meet

a face that you know; and when all the faces you

did know seem to have been dead faces, disappeared

for an indefinite time. I have not travelled

enough the last eight years, I suppose: it does

not do to become attached insensibly to places

and persons. ... I suppose you have had some

postal cards from me; and you are beginning to think I am writing quite often. I suppose I am,

and you know the reason why; and perhaps you

are thinking to yourself: 'He feels a little blue

now, and is accordingly very affectionate, &c.;

but by and by he will be quite forgetful, and perhaps

will not write so often as at present.

Well, I suppose you are right. I live in and

by extremes and am on an extreme now. I write

extremely often, because I feel alone and extremely

alone. By and by, if I get well, I shall

write only by weeks; and with time perhaps only

by months; and when at last comes the rush

of business and busy newspaper work, only by

years, - until the times and places of old friendship

are forgotten, and old faces have become

dim as dreams, and these little spider-threads of

attachments will finally yield to the long strain

of a thousand miles."

Facsimile and text from Letters from the Raven, edited by Milton Bronner, 1907

NEW ORLEANS 1877 - 1889

November 13, 1877, finds Hearn overjoyed

in New Orleans. He would stay in New Orleans for 13 years fighting for his life. His letters to Henry Watkin in Cincinnati tell the story.

New Orleans, Canal Street in 1898, Photo Wikipedia.

In 1881, Hearn succeeded in becoming a member of the

staff of the leading New Orleans paper, the "Times Democrat". With Page Baker, the owner and editor-in-chief of the paper, he formed a salutary and enduring friendship.

Nina Kennan, in her biography of Hearn describes him:

"At this time he was

about five feet three inches in height, his complexion clear

olive, his hair straight and black, his salient features a

long, sharp, aquiline nose and prominent near-sighted eyes,

the left one, injured at Ushaw, considerably more prominent

than the other. In his sensitive, morbid fashion he greatly

over-exaggerated the disfiguring effect this had on his personal

appearance. When engaged in conversation, he habitually

held his hand over it, and was always photographed

in profile looking down."

How much of this description is myth? - An - obviously professional - portrait from the end of the eighties shows him as a conceited Spanish dandy but certainly not destitute:

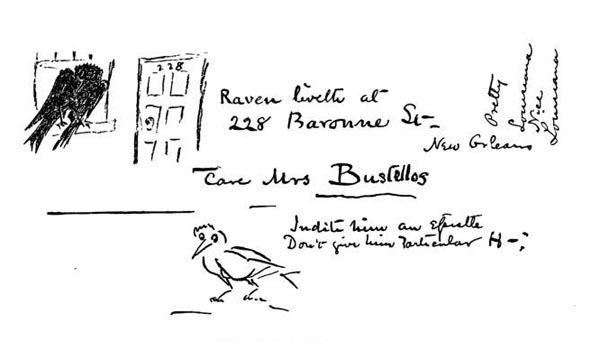

LETTERS FROM THE RAVEN 1878-90

Hearn's Letters from the Raven to Henry Watkin become the diary of his years in New Orleans. Another drawing on a postcard anounces his overjoyed arrival in that city November 13, 1877.

Watkin was busy and couldn't answer immediately. Hearn sent him this black postcard (Nov. 29, 1877):

When the reply finally came Hearn wrote a long letter describing his dire situation but also of the delights of New Orleans.

Undated, December 1877

"DEAR OLD FRIEND: I cannot say how glad

I was to hear from you. I am slowly, very slowly, getting

better.... The wealth of a world is here, - unworked

gold in the ore, one might say; the paradise of

the South is here, deserted and half in ruins. I

never beheld anything so beautiful and so sad.

When I saw it first - sunrise over Louisiana -

the tears sprang to my eyes. It was like young

death, - a dead bride crowned with orange flowers, - a dead face that asked for a kiss.

I cannot say

how fair and rich and beautiful this dead South

is. It has fascinated me. I have resolved to live

in it; I could not leave it for that chill and damp

Northern life again. Yes ; I think you could make

it pay to come here. One can do much here with

very little capital. The great thing is, of course,

the sugar-cane business. Everybody who goes

into it almost does well. Some make half a million

a year at it. The capital required to build a sugar

mill, &c., is of course enormous; but men often

begin with a few acres and become well-to-do in

a few years. Louisiana thirsts for emigrants as a

dry land for water. I was thinking of writing to

tell you that I think you could do something in

the way of the fruit business to make it worth

your while to come down, - oranges, bananas, and

tropical plants sell here at fabulously low prices.

Bananas are of course perishable freight when

ripe; but oranges are not, and I hear they sell at

fifty cents a hundred, and even less than that a

short distance from the city. So there are many

other things here one could speculate in. I think

with one partner North and one South, a firm

could make money in the fruit business here. But

there, you know I don't know anything about business. What's the good of asking ME about

business?

If you come here, you can live for almost nothing.

Food is ridiculously cheap, - that is, cheap

food. Then there are first-class restaurants here where the charge is three dollars for dinner. But

board and lodging is very cheap. . . .

I have written twice to the Commerical, but

have only seen one of my letters, - the Forest

letter. I have a copy. I fear the other letters will

not be published. Too enthusiastic, you know.

But I could not write coolly about beautiful Louisiana. . . .

Oh, you must come to New Orleans sometime, - no nasty chill, no coughs and cold. The

healthiest climate in the world. Eternal summer.

It is damp at nights however, and fires are lit

of evenings to dry the rooms. You know the land

is marshy. Even the dead are unburied, - they are

only vaulted up. The cemeteries are vaults, not

graveyards. Only the Jews bury their dead; and

their dead are buried in water. It is water three -

yes, two - feet underground.

I like the people, especially the French; but

of course I might yet have reason to change my

opinion. . . .

Would you be surprised to hear that I have

been visiting my UNCLE? Would you be astonished

to learn that I was on the verge of poverty ?

No. Then, forsooth, I will be discreet. One

can live here for twenty cents a day - what's the

odds? . . .

Yours truly,

THE PRODIGAL SON"

Hearn's letters from New Orleans are such a delight to read that I copied a few more.

After a seven months' hunt for work Hearn

saw some of the hardest times of his life in New

Orleans. The situation, as he described it in the following

letter to Watkin, could not have been worse

than when, as a waif, he wandered the streets

of London.

Postmarked June 14, 1878.

"DEAR OLD MAN: Wish you would tell me

something wise and serviceable. I'm completely

and hopelessly busted up and flattened out, but

I don't write this because I have any desire to

ask you for pecuniary assistance, have asked

for that elsewhere. Have been here seven months

and never made one cent in the city. No possible

prospect of doing anything in this town now

or within twenty-five years. Books and clothes

all gone, shirt sticking through seat of my pants, -

literary work rejected East, - get a five-cent

meal once in two days, - don't know one night

where I 'm going to sleep next, - and am d --d

sick with climate into the bargain. Yellow fever

supposed to be in the city. Newspapers expected

to bust up. Twenty dollars per month is a good

living here; but it's simply impossible to make

even ten. Have been cheated and swindled considerably;

and have cheated and swindled others in retaliation. We are about even. D--n New

Orleans! - wish I'd never seen it. I am thinking

of going to Texas. How do you like the idea? -

to Dallas or Waco. Eyes about played out, I

guess. Have a sort of idea that I can be wonderfully

economical if I get any more good luck.

Can savefifteen out of twenty dollars a month -

under new conditions (?). Have no regular place

of residence now. Can't you drop a line to P. O.

next week, letting shining drops of wisdom drip

from the end of your pen?"

And this description of his ghastly self:

"DEAR OLD MAN: Somehow or other, when a

man gets right down in the dirt, he jumps up again.

The day after I wrote you, I got a position (without

asking for it) as assistant editor on the Item,

at a salary considerably smaller than that I received

on the Commercial (of Cincinnati), but large

enough to enable me to save half of it. Therefore

I hasten to return Will's generous favor with

the most sincere thanks and kindest wishes. You would scarcely know me now, for my face is thinner

than a knife and my skin very dark. The

Southern sun has turned me into a mulatto. I

have ceased to wear spectacles, and my hair is wild

and ghastly. I am seriously thinking of going into

a fraud, which will pay like hell, - an advertising

fraud: buying land by the pound and selling

it in boxes at one dollar per box. I have a party

here now who wants to furnish bulk of capital

and go shares. He is an old hand at the dodge.

It would be carried along under false names, of

course; and there is really no money in honest

work. ... I think I shall see you in the fall or

spring; and when I come again to Cincinnati, it

will be, my dear old man, as you would wish, with

money in my pocket. It did me much good to

hear from you ; for I fancied my postal card asking

for help might have offended you; and I

feared you had resolved that I was a fraud. Well,

I am something of a fraud, but not to everybody. ...

I don't like the people here at all, and

would not live here continually. But it is convenient

now, for I could not live cheaper elsewhere"

Letters from Dryades Street 1880-82

1881-82 Hearn jointly with a partner finally opened a restaurant - "to make money off the poorest" he writes to Watkin. He reports to Henry in a most sarcastic letter.

"MY DEAR OLD MAN : Your style of correspondence -

four letters a year - leads me to suppose

that the fate of the Raven is of little consequence.

It was therefore with surprise that I

heard of a letter concerning It being received

at the Item office. The letter warranted the assumption

that you had at least some curiosity, if

nothing better, in regard to It. That curiosity

should be gratified. The Raven keepeth a restaurant

in the city of New Orleans. It is secretly in

business for itself. It is also in the newspaper

business. The reason It has gone into business

for itself is that It is tired of working for other people. The reason that It is still in the newspaper

line is that the business is not yet paying,

and needs some financial support. The business

is the cheapest in N. O. All dishes are five cents.

Knocks the market price out of things. The

business has already cost about one hundred

dollars to set up. May pay well; may not. The

Raven has a partner, - a large and ferocious man,

who kills people that disagree with their coffee.

The Raven expects to settle in Cuba before long.

Is going there to reconnoitre in a few months, -

if Fortune smileth. It has mastered the elements

of Spanish language, and has a Spanish tutor

who comes every day to teach It.

The Raven would not objecl: to see the O.M.

again, - on the contrary, he is filled with CURIOSITY

to see him. The Raven may succeed right

off. He may not. But he is going to succeed

sooner or later, even if he has to start an eating-

house in Hell. He sends you his respedts, - reserving

his affection for a later time."

Hearn enclosed a yellow handbill

advertising his restaurant.:

"THE 5-CENT RESTAURANT

160 Dryades Street

This is the cheapest eating-house in the South. It is neat,

orderly, and respectable as any other in New Orleans. You

can get a good meal for a couple of nickels. All dishes 5

cents. A large cup of pure Coffee, with Rolls, only 5 cents.

Everything half the price of the markets. "

The venture ended as might have been expected.

Hearn had not inherited the commercial instincts of his ancestors, his

partner robbed him of all the money he had invested,

and decamped, leaving him saddled with the restaurant

and a considerable debt. A swindling building

society seems to have absorbed the rest of his

savings.

Facsimiles and excerpts from Letters from the Raven, edited by Milton Bronner, 1907

GRAND ISLE 1884

In 1884 Hearn went to Grande Isle, in the Archipelago

of the Gulf, for his summer holiday.

He lived in the shack on the left. The center of the group of the vaguely discernable young people may be Elizabeth Bisland.

It was during this visit to Grande Isle that he wrote "Chita". Fostered by Elizabeth Bisland Chita appeared in Harper's Magazine under the title of "Torn Letters"

CHITA - THE STRENGTH OF THE SEA

"At a

hasty glance, the general appearance of this marsh verdure is vague enough, as

it ranges away towards the sand, to convey

the idea of amphibious vegetation, -

a primitive flora as yet undecided

whether to retain marine habits and

forms, or to assume terrestrial ones ; -

and the occasional inspection of surprising

shapes might strengthen this fancy:

Queer flat-lying and many- branching

things, which resemble sea-weeds in juiciness

and color and consistency, crackle

under your feet from time to time; the

moist and weighty air seems heated rather

from below than from above, - less by

the sun than by the radiation of a cooling

world ; and the mists of morning or

evening appear to simulate the vapory

exhalation of volcanic forces, - latent, but

only dozing, and uncomfortably close to

the surface.

The family of a Spanish fisherman, Feliu Viosca, once occupied and gave its

name to such an islet, quite close to the

Gulf-shore, - the loftiest bit of land along

fourteen miles of just such marshy coast. Landward, it dominated

a desolation that wearied the eye

to look at, a wilderness of reedy sloughs,

patched at intervals with ranges of bitter-

weed, tufts of elbow-bushes, and broad

reaches of saw-grass, stretching away to

a bluish-green line of woods that closed

the horizon, and imperfectly drained in

the driest season by a slimy little bayou

that continually vomited foul water into the sea.

Savage fishermen, at some unrecorded

time, had heaped upon the eminence a

hill of clam-shells, - refuse of a million

feasts; earth again had been formed over

these, perhaps by the blind agency of

worms working through centuries unnumbered;

and the new soil had given

birth to a luxuriant vegetation.

Millennial

oaks interknotted their roots below

its surface, and vouchsafed protection to

many a frailer growth of shrub or tree, -

wild orange, water-willow, palmetto, locust,

pomegranate, and many trailing tendrilled things, both green and gray.

Then, -

perhaps about half a century ago,- a few white fishermen cleared a place for

themselves in this grove, and built a few

palmetto cottages, with boat-houses and

a wharf, facing the bayou. Later on this

temporary fishing station became a permanent

settlement : homes constructed

of heavy timber and plaster mixed with

the trailing moss of the oaks and cypresses

took the places of the frail and fragrant

huts of palmetto.

Still the population

itself retained a floating character :

it ebbed and came, according to season

and circumstances, according to luck or

loss in the tilling of the sea. Viosca, the

founder of the settlement, managed to do well.

He owned several luggers and sloops,

which were hired out upon excellent

terms; he could make large and profitable

contracts with New Orleans fish-dealers;

and he was vaguely suspected of possessing more occult resources.

There

were some confused stories current about

his having once been a daring smuggler,

and having only been reformed by the

pleadings of his wife Carmen, - a little

brown woman who had followed him

from Barcelona to share his fortunes in

the western world.

On hot days, when the shade was full

of thin sweet scents, the place had a

tropical charm, a drowsy peace. Nothing

except the peculiar appearance of the line

of oaks facing the Gulf could have conveyed

to the visitor any suggestion of

days in which the trilling of crickets and

the fluting of birds had ceased, of nights

when the voices of the marsh had been

hushed for fear. In one enormous rank

the veteran trees stood shoulder to shoulder,

but in the attitude of giants overmastered, -

forced backward towards the prostrate trees ; but the rest of the oaks stood on, and strove in line, and saved

the habitations defended by them. . . .

Before a little waxen image of the

Mother and Child, - an odd little Virgin

with an Indian face, brought home by

Feliu as a gift after one of his Mexican

voyages. - Carmen Viosca had burned

candles and prayed; sometimes telling

her beads; sometimes murmuring the

litanies she knew by heart; sometimes

also reading from a prayer-book worn and

greasy as a long-used pack of cards. It

was particularly stained at one page, a

page on which her tears had fallen many

a lonely night - a page with a clumsy

wood-cut representing a celestial lamp, a

symbolic radiance, shining through darkness,

and on either side a kneeling angel.

Photo and excerpts from Lafcadio Hearn, "Chita. The Legend of l'Isle Derniere," 1922

THE GREAT HURRICANE 1884

Before the storm, Grand Island.

Photo

Panoramio

The high point of Chita is his description of the Great Hurricane:

A MEMORY OF "LAST ISLAND"

1884

Je suis la vaste melee, —

Reptile, etant Fonde ; ailee,

Etant le vent, —

Force et fuite, haine et vie,

Houle immense, pour suivie

Et pour suivant. —

VICTOR HUGO.

"Sometimes on autumn evenings, when the

hollow of heaven flames like the interior of a chalice,

waves and clouds are flying in one wild rout of

broken gold....

....In the half-lull between two terrible gusts there

came a sound that seemed

strange in that night of multitudinous terrors -

a sound of music!

Almost every evening throughout the season

there had been dancing in the great hall; - there

was dancing that night also. The population of the

hotel had been augmented by the advent of families from other parts of the island, who found their

summer cottages insecure places of shelter: there

were nearly four hundred guests assembled.

Perhaps

it was for this reason that the entertainment

had been prepared upon a grander plan than usual,

that it assumed the form of a fashionable ball. And

all those pleasure- seekers mingled

joyously.

Half an hour might have passed; still the lights

flamed calmly, and the violins trilled, and the perfumed

whirl went on. . . . And suddenly the wind

veered!

Again the ship reeled, and shuddered, and turned,

and began to drag all her anchors. But she now

dragged away from the great building and its lights -

away from the voluptuous thunder of the grand

piano - even at that moment outpouring the great

joy of Weber's melody orchestrated by Berlioz:

"l'Invitation a la Valse" - with its marvelous musical

swing! ....

Suddenly someone shrieked in the midst of the revels; -

some girl who found her pretty slippers wet.

What could it be? Thin streams of water were

spreading over the level planking - curling about

the feet of the dancers. . . . What could it be? All

the land had begun to quake, even as, but a moment

before, the polished floor was trembling to the

pressure of circling steps; - all the building shook

now; every beam uttered its groan. What could

it be? . . . For a moment there was a ghastly hush of voices.

And through that hush there burst upon the ears of

all a fearful and unfamiliar sound, as of a colossal

cannonade - rolling up from the south, with volleying

lightnings.

One crash ! - the huge frame

building rocks like a cradle, seesaws, crackles. What

are human shrieks now? - the tornado is shrieking!

Another! - chandeliers splinter; lights are dashed

out; a sweeping cataract hurls in: the immense hall

rises - oscillates - twirls as upon a pivot - crepitates -

crumbles into ruin. Crash again! - the

swirling wreck dissolves into the wallowing of another

monster billow; and a hundred cottages over-turn, spin in sudden eddies, quiver, disjoint, and

melt into the seething. ...

So the hurricane passed - tearing off the

heads of the prodigious waves, to hurl them a hundred

feet in air - heaping up the ocean against the

land - upturning the woods. Bays and passes were

swollen to abysses; rivers regorged; the sea-marshes

were changed to raging wastes of water. Before New

Orleans the flood of the mile-broad Mississippi rose

six feet above highest water-mark.

And over roaring Kaimbuck Pass - over the

agony of Caillou Bay - the billowing tide rushed

unresisted from the Gulf - tearing and swallowing

the land in its course - ploughing out deep-sea

channels where sleek herds had been grazing but a

few hours before - rending islands in twain - and

ever bearing with it, through the night, enormous

vortex of wreck and vast wan drift of corpses. . . .

But the ship remained....

Next morning, as the tremendous tide withdraws its plunging

waters, all the pirates of air follow the great white-

gleaming retreat: a storm of billowing wings and

screaming throats.

And swift in the wake of gull and frigate-bird the

Wreckers come, the Spoilers of the dead - savage

skimmers of the sea - hurricane-riders wont to

spread their canvas-pinions in the face of storms;

Sicilian and Corsican outlaws, Manila-men from

the marshes, deserters from many navies, Lascars,

marooners, refugees of a hundred nationalities -

fishers and shrimpers by name, smugglers by

opportunity - wild channel-finders from obscure

bayous and unfamiliar chenieres, all skilled in the

mysteries of these mysterious waters beyond the

comprehension of the oldest licensed pilot. . . .

There is plunder for all - birds and men. There

are drowned sheep in multitude, heaped carcasses of

kine. There are casks of claret and kegs of brandy

and legions of bottles bobbing in the surf. There are

billiard-tables overturned upon the sand; - there

are sofas, pianos, footstools and music-stools,

luxurious chairs, lounges of bamboo. There are

chests of cedar, and toilet-tables of rosewood, and

trunks of fine stamped leather stored with precious

apparel. There are objets de luxe innumerable.

There are children's playthings: French dolls in

marvelous toilets, and toy carts, and wooden horses,

and wooden spades, and brave little wooden ships

that rode out the gale in which the great Nautilus went down. There is money in notes and in coin -

in purses, in pocketbooks, and in pockets: plenty of

it! There are silks, satins, laces, and fine linen to

be stripped from the bodies of the drowned - and

necklaces, bracelets, watches, finger-rings and fine

chains, brooches and trinkets. . . . "Chi bidizza! -

Oh! chi bedda mughieri! Eccu, la bidizza!"

Thrice the great cry rings rippling through the

gray air over the green sea, over the far-

flooded shell-reefs, where the huge white flashes are

sheet-lightning of breakers, and over the weird

wash of corpses coming in. It is the steam-call of the relief-boat, hastening to rescue the living, to gather in the dead.

The tremendous tragedy is over!"

CHITA

Feliu Viosca

"Out of the debries of the Huricane, Feliu Viosca, a local fisherman rescued a half-drowned, four-year old girl and revives her. She has blond hair and speaks a few sentences of local French patois. . Her mother is dead. Nobody has ever seen the blond creature. The fisherman and his wife Carmen raise her like a gift from Heaven. They name her Chita - Conchita Viosca."

Many years later Julien La Brierre comes to the forlorn village on Grand Isle during an attack of Malaria. - The fisherman's wife nurses him, and in his delirium he recognizes Chita as his lost daughter....

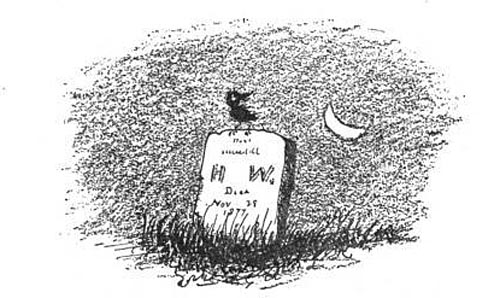

Hearn leaves the end open. We don't find out whether Julien dies or departs with his child... The novella, inspired by a grave stone in New Orleans, is full of wild, dramatic descriptions of the land and the hurricane. I have reproduced some parts, but left the heart-wrenching story of Chita alone.

See for yourself : Lafcadio Hearn, "Chita. The Legend of l'Isle Derniere,"

ELIZABETH BISLAND 1882

Elizabeth Bisland

In 1882 Hearn made the acquaintance of Elizabeth Bisland. She was about 16 when he first met her. She had a salaried position at the Orleans Times-Democrat for which she wrote poetry, stories and women articles. She struggled as much as Hearn, They recognized in each other

that close kinship of spirit which is the foundation of perfect friendship, and so long as he lived the relationship remained unclouded and unchanged beyond his death in 1904.(2)

There exist but a few letters between them though, mostly written 20 years later. In one from Japan he refers to those first

years of friendship:

"I remember nothing else -

only the sound of her voice - low and clear and at times like a flute: Her Voice and a Thought - multiple, both,

exceedingly - but justifying the imagination of une jeunne fille un

peu farouche (there is no English word that gives the same sense of shyness and force) who came into New Orleans from the country, and wrote nice things for the paper there, and was so kind to a particular savage that he could not understand - and

was afraid of."(3)

At the same time as Hearn was staying on Grand Isle Elizabeth was the center of a circle of young people there. But Lafcadio, as much as he was attracted by her, studiously avoided her. (1)

Soon after (1886) she accepted a position at Harper's in New York and fled from New Orleans - and their increasingly intimate relationship:...

As soon she was out of reach, he was able to write to her:

"So it was you and not I, that was to run away. . . . When I saw the charming notice about you in the Tribune there

suddenly came back to me the same vague sense of un-

happiness I had dreamed of feeling, - an absurd sense of

absolute loneliness. ... I thought I might be able to coax a photo-gravure from you ; but as you are never the same person two minutes in succession, I am partly consoled ; it would only be one small phase of you, Proteus, Circe, Undine, Djineeyeh! . . ." (4)

He visited her twice in New York, 1877 and in 1889 when he accepted an offer by Harper's to do a piece on the West Indies, which Elizabeth had got him, he wrote a last hurried note to her: "...I think I am right in going;

perhaps I am wrong in thinking of making the tropics a

home. Probably it will be the same thing over again:

impulse and chance compelling another change.

The carriage — no, the New York hack and hackman (no romance or sentimentality about these!) is waiting to

take me to Pier 49 East River. So I must end...." (4)

After Hearn had gone to Japan Elizabeth married a Mr. Witmore. There exist another 12 letters to Elizabeth from Hearn's last four years in Japan (1900-1904). Already before his death Elizabeth became the editor of several of Hearn's books, wrote a biography, and published some of his letters (4).

(1) The Grass Lark, A Study of Lafcadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Stevenson, 1998

(2) Elizabeth Bisland by Catherine Verdery. Library of Southern Literature, Vol 13, 1910

(3) Elizabeth Bisland, by Catherine Verdery, op. cit.

(4) More Letters to Elizabeth Bisland (search book for "Bisland"),

Elizabeth Bisland, 1906

NEXT: MARTINIQUE-WEST INDIES